Today we went with schoolchildren to study trees in my favorite park. There is a boy and a girl from Ukraine in this class. They don't speak German very well, so they don't communicate much with their classmates. They walked to the park next to me and I could hear them talking quietly among themselves.

The girl said "Why are they making us go count trees? How do you think is there any way we can ask to be excused from the class?"

The boy answered “There's no way they'd let us both go. But you wanted to ask this afternoon, didn't you?”

She said “Yeah, imagine you'd be here alone. Marina lives near here, maybe we can leave and stay in her place..."

They didn't talk to anyone else from the class, they walked to the back, as if hoping that they would be forgotten. Doomed to shake on the train and not wanting to get up at the stop.

They were about 14 years old.

I asked what they hate so much. Trees? Parks? Anything else?

They said they had no particular hatred for trees, although they liked forests better than parks. In fact, they already had plans for the evening, but Knut had ruined it for them with his three-hour tree count. I told them we'd only be walking for an hour, and there would be no need to count trees.

"What will we do then?" the girl asked.

I've gotten used to explaining what we do in English over the past six months, so finding Russian words suddenly put me on edge. I'm also used to quickly dealing with the stupor that now overtakes me everywhere.

So I said, “We will walk around the park and answer questions. Some trees in the park have QR codes on them. When you scan them, questions appear. When you answer them correctly, you'll know what kind of tree you're looking at”.

“I see”, the girl said. “Can we go home instead? Well, you see, we've already made plans…”

I said they could ask Knut about it when we got to the park. They got discouraged. Knut had been their teacher for two months and my boss for six months. All three of us realized there was no way for them to leave.

They began to weave behind the group even sadder, but then we reached the park. Not that I hoped the sight of the park would cheer them up, but as we entered the park path, which was like a tunnel of trees, their steps became more confident.

This is a very nice park. I come to it on my bike when I'm sad. I like both the park and the people who work here, and the festivals that are held here. There's even a piano and I sometimes come here to play.

It's the best place in the city I live in now. Even the teenagers, tired, tortured by the foreign language and stupid rules, immediately sensed something about this place. But of course, they didn't show it.

At the end of the path, Knut sat on a bench waiting for us, straight and imperturbable, like a statue. When he moved the girl, her name was Lera, said, "Oh, I thought it was some kind of statue!". Basically, he almost always gives that impression. He's very emotional, but he hides it amazingly well.

Knut spent a long time explaining to the whole class the rules of the game: how to look for trees, how to use the rope to measure the trunk, how to divide into teams, and what to do if you get lost in the park.

The whole class listened attentively. My two new acquaintances carefully pretended not to understand German. Knut noticed it and asked me to translate to them everything he said. The problem with my translation was that I didn't even pretend not to understand German.

Besides, I had already explained the rules of the game to them and had already realized that instead of following the rules, they were planning to sit on some distant bench. Then everyone split into teams and Knut suggested that I join Lera and Vadim's team to help translate the questions. I could literally hear the plans to sit out instead of play collapsing in their heads and prepared for a serious test of our nerves. So we walked together to the nearest tree.

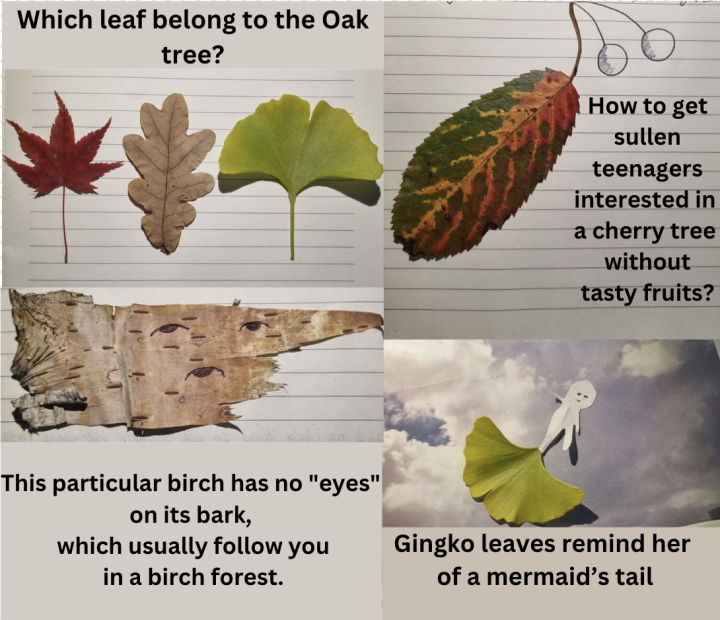

The first tree was a cherry plum. I had no idea how to get sullen teenagers interested in a cherry plum in October when it has no tasty fruit. My only memory of it was a garden in a cottage in the Crimea, in which I went out for a walk in the mornings when I was 5 years old. There grew cherry plums, cherries, raspberries, and in the evenings ferrets and hedgehogs crawled out.

It turned out that Lera knew a cherry plum, it also grows in her garden.

The next tree was a sweet cherry, and Lera immediately recognized it, too, by the ring-shaped pattern on its bark. She quickly answered the questions for each tree - choosing the correct bark pattern from the answer choices, noting the type of leaves, and measuring the trunk with a rope.

She didn't recognize the birch tree right away, because it is probably too northern species. It was also difficult to choose the right bark pattern from 4 answers because this particular birch has no "eyes" on its bark, which usually follow you in a birch forest. I told them about the birch trees' gaze and they had to take my word for it.

After a few trees, Lera admitted that it wasn't as boring as she expected and asked Vadim if he liked it. Vadim would have liked it if only he hadn't been forced to do it after school. I agreed with him and told him that my studies at the biological university were full of such walks and when I told my friends about it, they always said that it seemed interesting. But when exam grades depend on how many trees, birds, and insects you can recognize, it feels much more boring than when you do it for fun.

Lera had a story from her childhood about every tree we met on the route. She and her friends made a bungee cord on a willow tree and swung on it until their parents scolded them. “Helicopters” from the maple tree she wore on her upper lip, imagining they were mustaches. The unusual Gingko leaves she sees for the first time, but they remind her of a mermaid's tail. She likes to draw on the pavement with horse chestnut fruits, and walnuts are her favorite food, but when you peel them off, they stain your hands brown and are hard to wash.

The last trees we scanned were two ash trees named Ronia and Birk. Lera didn't have any stories about the ash trees, so I recounted to her and Vadim the plot of the book "Ronia, the Robber’s Daughter," after the characters of which we named all the trees on this route.

We finished second, so we didn't get the chocolate promised to the winners. But Ronia and Birk weren't upset at all. Like Ronia in the book, they were learning not to be afraid of the forest and boring games.

I said goodbye to them and decided to stay in the park longer. I helped paint the trunks of some trees with a special glue mixed with sand to protect them from beavers. They've gotten quite brazen lately and have already seriously gnawed some of the trees in the park.

When I started my project, the trees didn't seem particularly interesting to me. I didn't know much about trees and didn't really want to learn about them. I was more interested in listening to the birds, recognizing familiar voices, and telling everyone around me about what I was hearing from these old friends of mine. Now they've flown south and I think I'm starting to recognize the trees better. They don't fly anywhere and they grow long and slow in the same place. Maybe I'll learn to do it one day.